German-American Relationships & Romances

Despite the early “Anti-Fraternization Order,” some private relationships existed nevertheless. Since many German men had been killed during the war, were crippled or suffered from post-traumatic stress, the German “Fräuleins” were attracted to the good-looking Doughboys. While the majority of the civilian population suffered from poverty and hunger, the Americans lived in plenty, with enough money to indulge the young women.

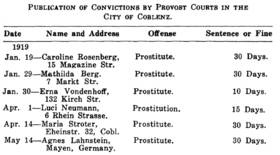

- Compilation of several cases of prostitution in Koblenz. While most American-German crimes were handled by the U.S. Provost Courts, cases of prostitution were handled by specially-created Vagrancy Courts. (Report of the Military Commander Coblenz, Germany, from December 8, 1918, to May 22, 1919. Fort Leavenworth 1921).

In Koblenz, the local authorities were concerned about the liberal nature of many women and often made serious negative comments in their official records, stating, for example: “Slept with Americans,” thus being suspect of prostitution. The distinction between prostitution and romantic love was difficult to determine.

Even when the “Anti-Fraternization Order” had finally been revoked, both German and American authorities remained skeptical about these relationships. After a short while, the first German-American children, the so-called “Amerikanerkinder,” were born. Special regulations were enforced for couples intending to marry as a result of having a child. In Koblenz the U.S. Command allowed some 1,200 marriages of German women to Doughboys. Some Doughboys took their new wives and children back home to the U.S.

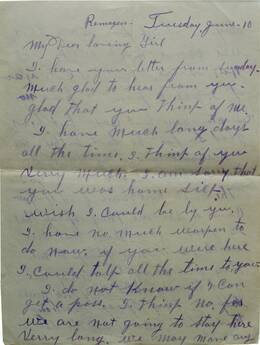

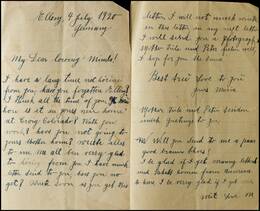

- Love letters between an American Doughboy and his German fiancé. The German girlfriend’s letter was written probably intentionally on July 4, 1920. Obviously the author had been learning English for only a short while. Meanwhile, her lover had returned to the U.S. What she didn’t mention in the letter was that she had given birth to their child earlier in March 1920 (private collection).

This was the case for American author Charles Bukowski (1920–1994), who was born to an American father and a German mother in Andernach in 1920, and moved to the United States in 1923. Others, however, did not want to get married, instead leaving girlfriends and children in the Rhineland – though sometimes they were nevertheless forced to pay alimony.

After the departure of the American Forces, many illegitimate children remained in the Rhineland. Comments can be found on the birth records located in the Koblenz archives, with names such as William, John or Henry. In the city of Koblenz alone, there were some 200 currently-known German-American children, though the real number was probably much higher. While the rate of illegitimate children was 8% prior to World War I, it reached 20% after the war. To this day, no one knows the actual total number of these children. The so-called “Amerikanerkinder” were a major concern for both sides. The support provided by several local agencies had to be coordinated, especially for poverty-stricken single mothers.

General Allen and the “American Committee for Relief of German Children” systematically collected funds for poor children and mothers. Other aid organizations, such as the Red Cross, did their part, although not all received support, since numerous women lacked the courage to make their situation known. Especially in small villages, shame and fear, along with the social stigma and religious belief overshadowed this problematic reality. Many family ties with American relatives therefore remain forgotten.

Today, modern technology like DNA-analysis and genealogical data bases such as provided by Ancestry, along with historical research, can locate family members even a century later. This was the case for Johannes Heibel’s father: Only in 2001 did he tell Johannes that he was such an “Amerikanerkind” born in 1919. Johannes’ grandfather was, therefore, an American Doughboy. But Johannes did not have a family name, an address, or a military unit of his grandfather. All he had was a photo. Through historical research and the Ancestry DNA analysis, he managed to find his ancestors – 100 years after the end of World War I, the two families were brought together.

THE STORY OF REMAGEN

During World War II, such an “Amerikanerkind” would play a prominent role in history: Karl Heinrich Timmermann, who was born in Frankfurt in 1922. His German mother and American father married and later moved to Nebraska. On March 7, 1945, Lt. Timmermann, then an American officer serving in the 27th Armoured Infantry Division, successfully led his unit across the famous Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen. An “American child” from WWI became one of the first GIs to cross the Rhine River – the same bridge the Doughboys had crossed before in 1918.

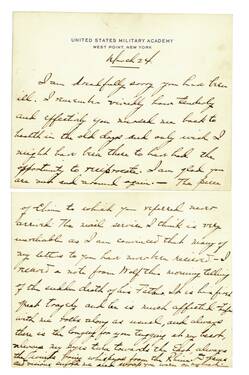

The Beauty and the General

One of the most prominent American military leaders of the United States also had a romantic affair in the Rhineland: Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964). As the commander of the 84th Infantry Brigade after the war he was lodged with his staff in the Villa Schönberg in Sinzig. Here, he fell in love with Herta Heuser, the landlord’s daughter, who nursed him back to health while he was recuperating from the aftereffects of his war injuries. Upon receiving orders to return to the United States in April 1919, MacArthur gave a grand farewell dinner, to which he invited Herta Heuser. Their relationship clearly violated the “Anti-Fraternization Order,” however. Until 1921, he regularly wrote poetic love letters to the charming German lady, who did not wish to immigrate to the U.S. In 1922, General MacArthur married an American, Louise Cromwell Brooks (1890–1965).