In a Strange Land – the First Months

- Captain Earl Almon, Commander of the M Company of the 16th Infantry Regiment announces the order of the day to the mayor and an official in Leuterod in the Westerwald. Guessing from this scene from 1919, Earl Almon probably had some knowledge of the German language (Courtesy of the 16th Infantry Regiment Association).

By early 1919, some 250,000 Doughboys stood guard over an area of 2,510 square miles and a local population of 890,000. Providing housing for the American troops in the region was difficult. There were not enough barracks available for such a large force, so hotels and private homes soon had to be used to provide the soldiers with roofs over their heads. This forced quartering in the homes of civilians often caused misunderstandings and problems between soldiers and German inhabitants. Many Germans also felt that the rent they were paid was inadequate or that the Doughboys behaved too authoritatively.

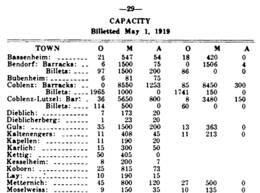

- Review of billeted U.S. troops. Distinctions were made between officers (“O”), men (“M”) and animals (“A”). German house owners were to be compensated per person and night: 2 Marks for officers, 40 Pfennigs for men including usage of beds, 10 Pfennigs for men without usage of beds (Report of the Military Commander Coblenz, Germany. From December 8, 1918, to May 22, 1919. Fort Leavenworth 1921).

Liaison Officers were assigned to supervise the local authorities, court rulings, economy, and political activities. Differences in language and bureaucratic systems were hard to overcome by both sides. Under the command of U.S. officers, armed local police helped enforce public order. However, the Americans controlled streets, trains, shipping routes, all means of communication and the border.

A so-called “Anti-Fraternization Order” prohibited any private contact between Germans and Americans, but was in reality difficult to enforce. The officers, as role models, obeyed this directive, while the Doughboys in the tight quarters of German homes followed it more liberally. The local Germans were soon relieved to discover their previous propaganda-based image proved inaccurate and the Doughboys often demonstrated themselves to be well disciplined and friendly. Many Americans and Doughboys had strong ties to Germany since their ancestors had emigrated over the preceding century, and at least some of them even still spoke German. The “Anti-Fraternization Order” was finally revoked on September 27, 1919.