The Press and Information Policies

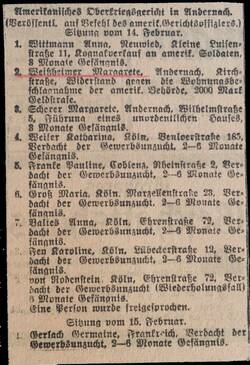

The U.S. military controlled and censored everything that was printed in the Rhineland, from pamphlets to books. Any negative comments resulted in heavy fines, a ban on publishing and even confiscation of publishing house equipment.

Beginning in Paris, February 1918, the “Stars & Stripes” newspaper was the most influential source of news, sports and command information for all Doughboys in Europe. Since local coverage was lacking, several smaller unit newspapers were soon published. The first was the “Fourth Corps Flare” in Mayen, noted as “the only American Newspaper printed in Germany.” Soon followed by the “Doughboy” for soldiers of the 7th Infantry Brigade in Adenau, beginning in March 1919, and the “Indian,” a weekly newspaper for the 2nd Division in Neuwied.

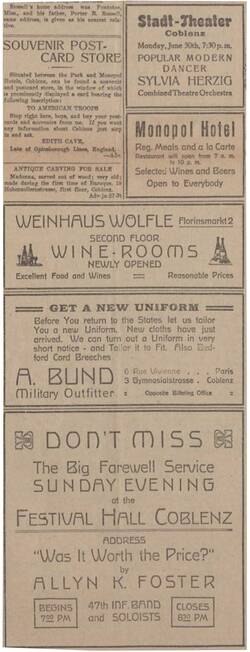

The main American newspaper in the Rhineland was the “Amaroc News” (the American Army of Occupation). Up to 60,000 copies a day were printed in Koblenz between April 1919 and the end of the occupation. The editors were friendly towards German opinions, and Germans sometimes wrote about their feelings in “Letters to the Editor.” Official announcements for the support of local communities in need symbolized an increasingly positive attitude towards the Germans. Local salesmen could place advertisements in the “Amaroc News.” These not only paid for its publication, but enticed the financially well-off Doughboys to shop in their stores or eat in the local restaurants.

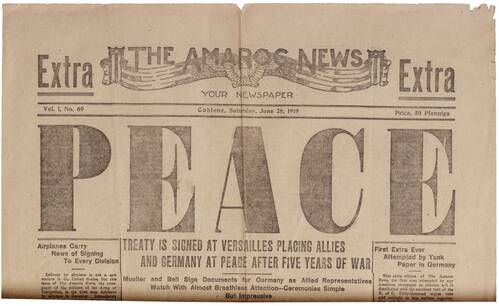

The Peace Messenger

On June 28, 1919, the victorious powers and Germany signed the Versailles Treaty. A few hours later, two U.S. pilots dropped around 40,000 copies of a special issue of the “Amaroc News” concerning the peace agreement over the American Zone to bring the joyful news immediately even to remote areas. One of the pilots, Captain Walter H. Schulze (1893–1919), crashed during this mission in Montabaur and died shortly afterwards of his injuries. Ironically, the “Peace Messenger” Captain Schulze became the last American to be killed during World War I. At the request of his parents, his body was transferred to the United States in 1920. In 1922 a memorial column was erected in his honor in Montabaur. The Nazi Regime destroyed this monument of remembrance at the end of the 1930s because it was too reminiscent of the “Shameful Peace of Versailles.” Schulze’s grave is now at West Point Military Cemetery in the U.S.